IT IS A PERIOD OF CIVIL WAR IN THE SUBCATEGORIZATIONAL EMPIRE

Here's another pickle: we've all been taught in Syntax 101 that nominal constituents and pronouns have something in common that sets them apart from (embedded) clauses. In more technical terms: nominal constituents and pronouns are DPs, while clauses are CPs. Some languages, like French, even wear this likeness on their sleeve, by using the same lexical items for their determiners (la table) and their pronouns (Je la vois.)

So far so good. Now let's take a look at subcategorization, in the simple, straight-from-Wikipedia sense of "the ability/necessity for lexical items (usually verbs) to require/allow the presence and types of the syntactic arguments with which they co-occur". If the bipartition between CPs and DPs sketched above is on the right track, we'd expect the subcategorization schemas (schemata?) of verbs to group pronouns and nominal constituents together and distinct from clauses. More generally, all things being equal—but are they ever?—we'd expect there to be four types of verbs:

Summing up, life is hunky-dory in the English-speaking parts the Subcategorizational Empire: pronouns and nominal constituents always work in tandem (either both present or both absent), and independently of sentential complements (all four cells of the logical space are filled). As it turns out, however, not everyone is so well-behaved. Let's now turn our attention to Dutch. At first sight, Dutch yields exactly the same four cells as English:

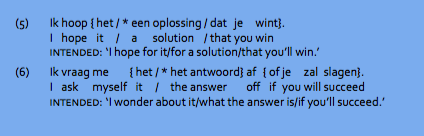

In addition to these four types, however, there is another:

These verbs—and others like them; this is a pretty common pattern—can be combined with pronouns and sentential complements, but not nominal constituents. Under the simple DP/CP-split sketched at the beginning of this post, this is quite mysterious. The generalization seems to be that there's no verb in Dutch—none that I could find anyway—that can select a clausal complement, but not a pronoun (which is why in order illustrate Type 3 (CPs but not DPs) before, I had to take recourse to a copular verb with an adjectival complement). At present I have no idea what is going on here: What does it mean for pronouns to pattern with clauses (in some contexts) in Dutch? Why does English differ from Dutch in this respect? Is this a difference in their pronominal or their verbal system (or both)? I also don't yet know if/how this pattern generalizes across the rest of Germanic: is the English pattern the default one or is the Dutch one, and are there other options? As you can see, there's plenty of stuff here to keep me occupied during the upcoming Christmas break. Should you want to give me a hand (and save me some time), feel free to let me know if/how your native language fits into this picture.

-

Ok, I've been taught this, and I hope the same holds for you.

-

And there's of course also the classic 1966 Postal-analysis of pronouns as nominal DPs that have undergone NP-ellipsis.

-

Yes, I got a little carried away with the nominal constituent in Type 2.

-

I realize that blij zijn 'to be happy' in Type 3 is technically not a verb, but bear with me; this will turn out to be important. Also, in case you're wondering about the word order here (or in example (6) below): given that blij 'happy' occupies roughly the same position as a clause-final verb in an embedded clause, we see the well-known fact kick in that Dutch is OV in embedded clauses with non-clausal objects, but VO with clausal objects. In all the other examples I can avoid this complication by V2'ing the verb out of the way.

-

My linguistic spidey sense tells me that this is case-related: somehow these pronouns seem less susceptible to the case filter, which allows them to occur in contexts where full DPs are not allowed. Let's assume there are not two, but three possible contexts when it comes to case assignment: (1) typical adjectives like blij 'happy' do not assign case at all and as a result only allow sentential complements, (2) verbs like hopen 'to hope' typically require a prepositional complement (like they do in English), but also have some residual case assigning capabilities and as a result are compatible with both pronouns and sentential complements, (3) fully case-assigning verbs like vertellen 'to tell' (or case-assigning adjectives like beu 'tired') are compatible with the whole gamut of complements.

-

Well, that and preparing the ultimate Christmas-Thanksgiving crossover dinner.